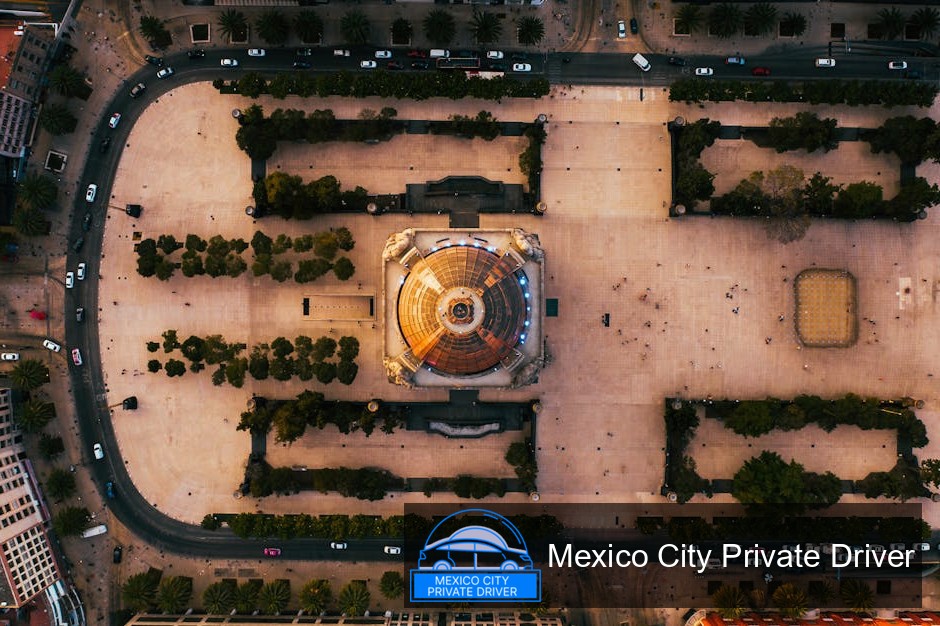

TL;DR The Monumento a la Revolución in Mexico City is an unfinished legislative dome turned national mausoleum and landmark. Built between 1910 and 1938, its 67 m (220 ft) copper dome and Art Deco legs symbolize both the Porfirian ambition and the upheaval of the Mexican Revolution. I’ve researched archival sources and visited the site: beneath the monument is a museum and crypt for revolutionary heroes, an elevator brings you to a 360° viewpoint, and the plaza functions as a civic stage for rallies and festivals. This guide covers history, architecture, practical visiting tips, and answers common questions.

Monumento a la Revolución Mexico City: A Complete Guide to Its History and Significance

Why I care about this monument

As someone who writes about cultural heritage and has spent time walking Mexico City’s central avenues, the Monumento a la Revolución strikes me as a rare structure that carries multiple stories at once: architectural ambition, interrupted politics, commemoration, and popular life. My research draws on municipal records, historical summaries, travel investigations and my on-site observations to synthesize a reliable portrait of the site (Mexico City government; Wikipedia; Atlas Obscura; BBC).

At a glance

- Location: Plaza de la República, near Paseo de la Reforma and Avenida de los Insurgentes (Cuauhtémoc borough).

- Height: commonly cited as 67 m / 220 ft.

- Construction period: initiated 1910; completed and inaugurated as a monument in the 1930s (final works around 1938; reinauguration/renovations noted in 2010).

- Current functions: monumental arch, mausoleum for revolutionaries, underground museum, public plaza and viewpoint.

- Access: open public space; museum access and elevator to the top may have specific hours and/or modest fees—most guide resources report free plaza access (check current official sources before visiting).

History: how a legislative palace became a revolution monument

The story begins before the Revolution. In the late 19th century Porfirio Díaz’s government planned an imposing Palacio Legislativo Federal to signal Mexico’s place among modern nation-states. French architect Émile Bénard produced the plans and construction of a massive domed structure began in 1910; Díaz himself laid the first stone that year (Mexico City government; Wikipedia).

Almost immediately, the Mexican Revolution shattered those plans. Díaz was ousted in 1911 and the political chaos that followed—assassinations, shifting power blocs and full-scale conflict—halted the legislative project. Although the new president Francisco I. Madero briefly funded work, the building was left incomplete as the Revolution entered its violent second phase (Mexico City government; BBC).

It was not until the 1930s that the abandoned palace found a new purpose. Architect Carlos Obregón Santacilia proposed converting the shell into a monument to the Revolution’s heroes. The structure was adapted and finished as we know it: a monumental arch and domed rotunda enclosing crypts and a public space. The monument opened in the late 1930s and was later renovated and re-inaugurated in the 20th and 21st centuries (Wikipedia; es.wikipedia).

Architectural identity: styles, materials and scale

The Monumento blends influences you wouldn’t expect in a single work: Beaux-Arts and Neoclassical planning (from the original French design), combined with 1930s Mexican Art Deco interventions by Obregón Santacilia. The result is a copper-dome crown supported by four massive “legs” with sculptural reliefs and Art Deco detailing. Observers often describe the dome as a transplanted church roof perched on high supports—an accurate visual shorthand for the building’s hybrid origins (Yucatán Magazine; GuanajuatoMexicoCity).

The official height often cited is 67 meters (220 feet), which is frequently noted in municipal materials and travel writing. Some sources also describe it as the world’s tallest triumphal arch, though phrasing varies among references (Wikipedia; Yucatán Magazine).

Mausoleum, museum and public uses

Beneath the monument there is an underground museum and crypt area that functions as a mausoleum for leading figures of the Revolution. Several coffins of revolutionaries were re-interred in the crypts as part of the monument’s symbolic role; the site thus operates both as memorial and as a place to learn about the Revolution’s complex history (GuanajuatoMexicoCity; Mexico City government).

Above ground, the plaza has become a civic arena—regularly used for cultural events, markets, rallies and public gatherings. At night the monument is illuminated and serves as a dramatic meeting point in the city’s urban fabric (Yucatán Magazine; ForeverVacation).

What to expect when you visit

From my visits, the Monumento offers a layered experience:

- Immediate visual drama: the bronze/copper dome and four massive pillars are visible from multiple avenues.

- Underground museum: contextual exhibits about the Revolution and the monument’s history—helpful for framing what you’re seeing aboveground (check museum hours before you go).

- Mausoleum crypts: solemn spaces commemorating revolutionary leaders.

- Viewpoint: an elevator (added during renovations) takes visitors up to a terrace where you can take in a 360-degree panorama of Mexico City.

- Public plaza life: vendors, weekend markets, and political demonstrations are common—it’s a living civic space, not just a monument.

Comparative snapshot: how the Monumento stacks up

| Monument | Height (approx.) | Primary function | Era / Style |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monumento a la Revolución (Mexico City) | 67 m / 220 ft | Mausoleum, memorial arch, public plaza | Beaux-Arts origins; Art Deco completion (1930s) |

| Arc de Triomphe (Paris) | 50 m / 164 ft | Triumphal arch, national memorial | Neoclassical (early 19th century) |

| Gateway Arch (St. Louis) | 192 m / 630 ft | Monument to westward expansion, observation deck | Modernist (mid-20th century) |

| Arch of Constantine (Rome) | 21 m / 69 ft | Ancient triumphal arch, imperial propaganda | Ancient Roman (4th century) |

Note: different sources sometimes classify “triumphal arch” or “memorial arch” differently; the Monumento’s claim to be the tallest depends on definitions and comparisons in various references (see Yucatán Magazine; Wikipedia).

Cultural and political significance

The Monumento is not only an architectural landmark; it’s a political text etched in stone and bronze. By converting an unfinished symbol of Porfirian central power into a mausoleum for revolutionaries, post-revolutionary leaders reframed the narrative of legitimacy. The monument thus marks both rupture and reconciliation: it recognizes the violence of the 1910s while offering a site for state-sponsored remembrance.

On the civic level, the plaza’s continued use for demonstrations and cultural events keeps the monument relevant. It’s a place where memory and everyday urban life intersect—vendors and protestors share a stage with tourists and school groups (Mexico City government; Yucatán Magazine).

Practical Guide

Below I give concrete steps for planning a visit based on current typical practice and my own visits; please verify current opening hours and services with official sources before you go.

How to get there

- Metro: take Line 2 (blue) to Revolución station—short walk to the plaza.

- Bus / RTP / Metrobús: several routes cross nearby avenues (Insurgentes, Reforma). Use a local transit app for real-time routing.

- Taxi / rideshare: drop-off at Plaza de la República; traffic can be heavy, especially during events.

Timing and what to bring

- Best times: early morning for quieter photos; golden hour for dramatic light; weekends for markets and livelier atmosphere.

- Bring: comfortable shoes (plaza paving), water, sunscreen, a camera, and a small amount of cash for vendors or museum tickets.

- Accessibility: the monument has elevators, but check current accessibility information if you require mobility accommodations.

Entry, museum and viewpoint

- Plaza access is free. The underground museum and elevator to the terrace may have limited hours and sometimes small fees or capacity limits—arrive early if you intend to ride the elevator (Atlas Obscura; ForeverVacation).

- Allow 60–90 minutes to combine the museum, crypt area, and a climb to the viewpoint.

Safety and etiquette

- The plaza is generally safe during daylight hours; usual urban precautions apply (watch belongings, avoid empty areas at night if alone).

- Respect the mausoleum spaces: maintain silence where required; follow signage.

- If attending a demonstration, be aware that events can be unpredictable—stay informed and keep a safe distance from police lines.

FAQs

Is the Monumento a la Revolución free to visit?

The plaza itself is free and open to the public 24/7. Access to the underground museum and the elevator to the viewpoint can have specific hours and, in some years, a small fee—check the official site or current visitor information before you go (ForeverVacation; Mexico City government).

Who designed the monument?

The original project was a legislative palace designed by French architect Émile Bénard. After the Revolution the shell was adapted into a monument by Mexican architect Carlos Obregón Santacilia in the 1930s, who gave it the form we recognize today (Mexico City government; Wikipedia).

Are the remains of famous revolutionaries actually there?

Yes. The crypts beneath the monument hold coffins of key revolutionary figures who were reinterred to make the site a national mausoleum. Sources describe the relocation of several leaders’ remains to the monument’s underground crypts, though specifics should be confirmed with the onsite museum materials for the most accurate list (GuanajuatoMexicoCity).

Can I go to the top for a panoramic view?

There is an elevator that takes visitors up to a terrace with panoramic views. This feature was added during renovations; access can be limited by hours or maintenance, so I recommend booking or arriving early on popular visiting days (Atlas Obscura; BBC).

When was the monument completed?

The conversion and finishing works that turned the abandoned legislative shell into the Monumento a la Revolución were completed in the 1930s, with the monument functioning as such by 1938. The site has undergone subsequent renovations and a notable re-inauguration in 2010 (es.wikipedia; BBC).

Are there guided tours available?

Yes—guided tours are periodically offered by municipal cultural programs, local guides, and private tour companies. A guided visit is useful for context about the Revolution and the monument’s architectural evolution; verify schedules in advance (Mexico City government; local tour resources).

Is the Monumento safe at night?

During my visits the immediate plaza felt active and well-lit at night, particularly around events. As with any urban center, avoid isolated areas and use common-sense precautions: stay in groups, keep valuables secure, and use reputable transportation if leaving late.

Final thoughts

Monumento a la Revolución is more than a tourist photo-op: it’s a layered historical text that reveals Mexico’s early-20th-century tensions, architectural ambitions, and civic life. Visiting the plaza, descending into the museum and crypt, and rising to the terrace gives a compact crash course in the Revolution’s physical and symbolic legacies. I encourage visitors to pair the monument with a walk along nearby Reforma to see how places of memory and power align in Mexico City.

If you want, I can also produce a printable one-page itinerary with times, transit options and a short checklist for visiting safely and efficiently.

Martin Weidemann is a digital transformation expert and entrepreneur with over 20 years of experience leading fintech and innovation projects. As a LinkedIn Top Voice in Digital Transformation and contributor to outlets like Forbes, he now brings that same expertise to travel and mobility in Mexico City through Mexico-City-Private-Driver.com. His focus: trustworthy service, local insights, and peace of mind for travelers.